Scholarly disciplines come into existence consequent upon the inborn interest human beings have for inquiry. We will now look briefly into the relation of Sufism to other scholarly disciplines under five categories.

Scholarly disciplines come into existence consequent upon the inborn interest human beings have for inquiry. Each of these disciplines investigates laws and principles regarding the realities in the area of its specialty. Through its investigation each discipline reaches, intentionally or unintentionally, certain points in common with Sufism, which itself incorporates and covers the same given field from broader perspective; that is from the vantage of wisdom. This mutuality is not relevant only to religious sciences, but also to all other sciences, theoretical and practical, ranging from fine arts to philosophy. In this relation, we will now look briefly into the relation of Sufism to other scholarly disciplines under five categories.

- SUFISM AND OTHER ISLAMIC DISCIPLINES

The purpose of religion is to make man acquainted with his Creator to mankind, to inform him of the obligations and responsibilities he has in Divine presence and to guide him to organize his social interactions in accordance with Divine will. Corresponding with this is the goal of Sufism; to lead a believer to this direction and endow him with a moral and spiritual strength to help him actualize these religious goals. Sufism also provides a spiritual background and explanation for the external aspects of religious commands and spiritually motivates a believer to offer his duties with a passionate sincerity and piety. As is therefore expected, the Sufi way is inextricably connected with all other branches of Islamic learning. An analysis of the intimate relation of Sufism with other Islamic disciplines will suffice to throw greater light on this fact.

Sufism and Theology

The subject matters of Islamic theology are primarily the Almighty’s essence, attributes and oneness. Since it is principally related to creedal topics, theology is regarded as the most important Islamic discipline (ashrafu’l-ulum). One of the basic goals of theology is establishing intellectual bases for endorsing true beliefs and rejecting false ones. Therefore, one of Islamic theology’s main functions is to respond to the critiques and opposition directed against Islam and to convince people of that Islam is a true and authentic religion revealed by the Almighty. The goal of Sufism is similar; it aims at knowing Allah, glory unto Him, Who has perfect attributes and is free from any kinds of defect, but through the heart.

Theology tries to find solutions to creedal issues on the basis of the Quran and Sunnah and by use of the human rational faculty. In this regard, theologians’ position may be comparable to that of philosophers. Yet, unlike the latter, the former do not use human reason independently from religion; instead, they put reason under the service of religion. Nevertheless, through its logical move from cause to effect, the rational faculty of man is not sufficient, on its own, to enable one to reach the truth. This is a journey of knowledge that requires the utilization of other means, first and foremost the heart.

Exactly at the point where reason arrives at a dead-end and cannot proceed to figure out the solution, the heart takes the lead and ensures man proceeds on this journey to see the solution for himself. In the Sufi path, these solutions manifest in the heart, in the form of spiritual unveilings and inspirations; and it goes without saying that the way in which these clarifying solutions are comprehended must be in agreement with the Quran and Sunnah. Eventually, at the end of this epistemological process, Sufism leads a servant to a satisfactory finale.

To be sure, Muslim theologians also acknowledge the necessity of the heart as an authentic instrument of knowledge. In this regard, as has already been mentioned, they differ from philosophers, the majority of whom acknowledge only the faculty of reason as an instrument of knowledge. Historically speaking, there are many theologians who theoretically acknowledge the validity of spiritual explanations, not to mention many others to have personally practiced the Sufi way.

In effect, the mental activity of man, his reason and judgment, are always derived from the sensory impressions received from the material world. He thus tries to reach the truth by means of drawing similarities and discerning opposites. Reaching and grasping, however, the existence and realities of metaphysical beings, of which ordinary human mental activity does not have previous impressions, is impossible in this manner. The human faculty of reason, therefore, cannot satisfy man’s inborn inclinations towards reaching the Real, save to a limited extent. In relation to metaphysical realities, to which ordinary human reason does not have access, man can improve his level of intellectual satisfaction and perfect it through spiritual inspirations and manifestations that are impressed upon the heart. The main function of Sufism comes into existence at this point, for it provides an indispensable service to man in making him reach out to realities of a more advanced nature, which otherwise stand beyond the capacity of ordinary human reason. Sufism actualizes this possibility by invigorating man through Divine remembrance and thus renders the heart suitable to receive spiritual unveilings and inspirations. In this context, mainly with respect to the essential and performative attributes of the Almighty, Sufism is not only closely connected to Islamic theology; it further improves the theological explanations and hence human satisfaction, especially with regards to the metaphysical issues for which the human faculty of reason cannot provide sufficient answers.

Sufism addresses people in proportion to their intellectual capacities and enriches general theological arguments for the use and satisfaction of competent minds. It strengthens a person’s belief and conviction in the existence and oneness of the Almighty. Fakhruddin Razi, a prominent Muslim theologian and exegete, elucidates the relation between Sufism and Islamic theology and says, “Even though the methodologies of theologians are not sufficient enough to attain to reality, they are still the necessary first steps to be taken as a prelude to Sufism. Religious perfection can be attained through a healthy transition from exoteric religious sciences to the esoteric ones; the latter being based on knowledge of the underlying realities of things.”[1]

Sufism and Quranic Exegesis (Tafsir)

The science of Quranic exegesis explores the meanings of Quranic revelations and elaborates on them. The Holy Quran is a Divine guidance for mankind and its expressions comprise a depth of meaning. From this perspective, tafsir functions like a pharmacy for Sufism. Sufism aims at purifying and perfecting the inner dimension of man, an aim which the field of tafsir complements by providing the required prescriptions and medicine. In its application and analysis of topics, as well as in establishing its foundational methodology, Sufism relies principally on the Quran.

By offering instructions in every aspect of life, the Holy Quran leads mankind to attain to the pleasure of the Lord. It informs man the exact manner of leading a life dominated by the ever-present feeling of responsibility before the Almighty, of offering deeds of worship in the most sincere manner thinkable and pursuing life of piety adorned by an unremitting remembrance of the Divine. These considerations are equally central to the Sufi way.

As has already been underlined, the primary aim of a Sufi is to reach the Lord through the heart. And the authentic Sufi conception acknowledges the Holy Quran, the touchstone of human life, whose brilliant verse call for the deepest of all reflections, as the exclusive means to lead man to this direction. Reciting the Quran is an indispensable part of a Sufi’s life; it is the first thing he is required to do in the earliest hours of the morning. Capturing the subtle meanings conveyed by the Quranic verses, however, requires, in turn, a purified heart.

Since through his moral conduct the Blessed Prophet -upon him blessings and peace- was the Quran come-to-life, saints, being dedicated to moral perfection, strive to regulate every aspect of their lives in accordance with the ideal the Prophet –upon him blessings and peace- provided. By practicing and actualizing the Quran in every dimension of their lives, they become living Qurans in their own right.

As the Holy Quran is their main source of blessing and inspiration, Sufis have contributed immensely to tafsir literature, providing an invaluable service for enriching this literature through bringing the allegorical meanings of the verses of the Quran to light. Sufi commentators of the Quran have worked meticulously on unearthing the subtle meanings and inner wisdoms of Quranic expressions. Of course, their undertaking should not be confused with an attempt to imprison the illimitable Divine Words within limited human expressions; this was never their intention, insofar as a Sufi would never even think of devaluing the priceless expressions of the Quran. Furthermore, the Sufi methodology does not justify arbitrary and baseless interpretations. The general principles for a proper spiritual commentary as has been set by Sufi masters, is as follows:

1) The inner meaning posited for any given Quranic statement must not contradict the external message of the given verse.

2) The suggested meaning must have a place the general content of the Quran and Sunnah.

3) The wording and context of the given Quranic verse must be suitable for the proposed allegorical meaning.

As some authoritative examples of Sufi commentaries of the Quran, we may mention the Haqaiqu’t-Tafsir of Abu Abdullah Rahman as-Sulami, the Lataifu’l-Isharat of Qushayri and the Ruhu’l-Bayan of Ismail Hakki of Bursa. In addition to these complete commentaries of the Holy Quran, there are many others that include allegorical interpretations of specific Quranic verse, such as the works of Ibn Arabi and Rumi. Doubtless is the fact that the Quran is the inimitable word of the Almighty that has come directly from His attribute of Speech (kalam). Therefore, however competent a commentary may be, in the final reckoning, it is still a commentary; the reflections and words of a human being which cannot encompass the entirety of the semantic world of the Quran.

As human beings, we cannot completely understand the reality of the Almighty’s essence and attributes. Likewise is the case of understanding the Quran. Being a product of the Lord’s unique attribute of Speech, the Quran cannot be comprehended by any mind and rephrased by any tongue, however well-gifted they might be. Our grasp of the real meaning of the Quran might is comparable to taking a drop from a vast ocean; and this is highlighted by the Quran itself: “And if all the trees on earth were pens and the ocean [were ink], with seven oceans behind it to add to its [supply], yet would not the Words of the Almighty be exhausted [in the writing]; for The Almighty is Exalted in might and wisdom.” (Luqman, 27)

We might argue that the Almighty uses a higher level of speech to address human beings than their own conventional level, so that they could concentrate on the timeless and infinite aspects of Divine Speech and appreciate it in proportion to their level of understanding. The Blessed Prophet -upon him blessings and peace- explains this peculiarity of the Quranic style and states, “There is no end to the appearance of the Quran’s meanings.” (Tirmidhi, Fadailu’l-Quran, 14) Rumi says, in similar fashion that “…it is possible to transcribe the text of the Quran with a little amount of ink; but when it comes to expressing all the secrets comprised therein, an unlimited amount of ink of the size of immeasurable oceans would not suffice; nor would all the trees on earth as pens.”

The abovementioned Quranic and prophetic statements indicate that the Quran in fact comprises the entirety of all realities and truths in the form of a nucleus. Had this inner signification of the Quran been given an explicit mention, its size would exceed all boundaries. For this reason, the Quran mentions some truths in an explicit manner, while alluding to others only implicitly. Only those who are firmly grounded upon knowledge can discover these secrets; those who possess a profound insight to understand the realities embedded in the Quranic phrases and who execute its commands with a sound mind and heart.

Enumerating the scholarly qualifications required to embark upon an interpretation of the Quran, scholars of the methodology of tafsir include a branch they refer to as ‘God-given (wahbi) knowledge’, an expertise bestowed exclusively upon the exceptional servants of Allah, glory unto Him. This kind of knowledge is attained only by virtue of embodying piety, modesty and abstinence, and remaining in a ceaseless battle against the ego. Indicating this is a hadith which states, “Whoever practices that which he knows, the Almighty teaches him that which he does not know.” (Abu Nuaym, Hilya, X, 15) This effectively means that one cannot attain a portion of the secrets of the Quran, so long as he does not embark upon purifying from immoral traits and shortcomings like conceit, jealousy, love of the world, and so forth. For the Quran says, “I will turn My signs away from those who are arrogant on the earth without right.” (al-Araf, 146)

Sufism and the Sayings and Actions of the Blessed Prophet

-upon him blessings and peace- (Hadith–Siyar)

The science of hadith focuses on the sayings, actions, confirmations and physical and moral characteristics of the Blessed Prophet -upon him blessings and peace-. As is valid for all the other Islamic scholarly disciplines, hadith constitutes the second most important authoritative source for Sufism after the Holy Quran. Hadith collections contain authentic accounts of all aspects of the Prophet’s –upon him blessings and peace-life, be they physical, moral, and spiritual. From this perspective, it is not very hard to arrive at a conclusion that hadiths play a decisive role in the formation and development of Sufism. Hadiths that convey good moral qualities such as abstinence (zuhd), moral scrupulousness (wara), internalization of faith (ihsan), modesty (tawaddu), altruism (ithar), patience (sabr), gratitude (shukr), and trust in the Almighty (tawakkul) constitute the grounds of mystical theories and practices. These have a close relevance to Sufism, as they present the words and deeds of the Blessed Prophet -upon him blessings and peace-. It is there that the inseparable connection between Sufism and the science of hadith becomes most evident.

As was mentioned during the discussion of the relation of Sufism to Quranic exegesis, the foremost aim of Sufis is to seek closeness to and ultimately reach the Lord. They are aware that the journey of Divine love cannot be undertaken, except by following in the footsteps of the Blessed Prophet -upon him blessings and peace-. Sufis, therefore, follow the Prophet -upon him blessings and peace- under all circumstances and enjoy making use of the records of hadith that present glimpses of his exemplary words and deeds.

To follow the Blessed Prophet -upon him blessings and peace- is to feel an extreme love for him and to prefer him over everything else. There are many Quranic verses that underline the necessity of loving and obeying the Prophet -upon him blessings and peace. Concrete examples how one ought to love and obey the Blessed Prophet -upon him blessings and peace- can be found only in the scholarly sources of hadith and prophetic biography. Not only with respect to offering acts of worship and social interactions but also with respect to possessing good moral character traits, the Blessed Prophet -upon him blessings and peace- is the most perfect human being who ever graced this life. In detailing and confirming these fine aspects of the Prophet’s –upon him blessings and peace-works of hadith and prophetic biography are indispensable.

The meticulously recorded words of the Prophet -upon him blessings and peace- have come to our day, thanks to the narrative reliability of Muslim generations. In addition to his profound words, the actions and behavior of the Prophet -upon him blessings and peace- were also reported, in detail, by his Companions, and passed onto one generation after another to this day. The exemplary qualities observed in the conduct of great Sufis were inspired by none other than the Prophet’s -upon him blessings and peace- ideal characteristics; the pattern each believer must emulate as much as his capacity allows, since the Blessed Prophet -upon him blessings and peace- was sent as a perfect example for humankind entire. Those who can properly actualize this ideal are indeed exceptional individuals, for understanding the spirit of the Prophet’s –upon him blessings and peace- instructions and embodying them diligently in their lives. The fact that Sufis strive to lead people to this prophetic direction through their theoretical and practical teachings suffices to prove that they always act in accordance with the essence of the Sunnah.

The praiseworthy conduct of Sufis is but a reflection from the Prophet’s –upon him blessings and peace- typical qualities and living practices as transmitted in the textual records of hadith. From this vantage, the actions and behavior of exemplary Sufis are to be considered as the living commentaries of the words and conduct of the Blessed Prophet –upon him blessings and peace-. To put it in another way, by embodying the contents of the transmitted hadiths, Sufis uphold and perpetuate prophetic practices in different times and places.

Even before the appearance of Sufism as a scholarly discipline, both Sufis and scholars of hadith compiled works entitled Kitabu’z-Zuhd (The Book of Abstinence), which acts as a bridge connecting Sufism to the science of hadith.

On the other hand, Muslim mystics enriched the field of hadith by affording allegorical interpretations of various hadiths and expanding on their spiritual meanings. And although scholars of hadith have generally rejected this kind of possibility, some Sufis further argued that it was possible to personally receive hadiths from the Blessed Prophet -upon him blessings and peace- under his spiritual influence and command. According to this approach, this would occur through spiritual unveilings.

In Islamic intellectual history, we find many Sufi scholarly figures, like Hakim Tirmidhi and Kalabadhi, who presented works in the fields of both hadith and Sufism. Furthermore, there are many authorities in the field of hadith, who produced works in line with the Sufi methodology. The great Imam Bukhari -may Allah have mercy on him-, for instance, who compiled the most authoritative work in the field of hadith unanimously regarded as the second most important Islamic religious scripture after the Holy Quran – had an exemplary custom in writing down each hadith he had memorized. Before proceeding to transcribe each hadith, the Imam would perform two units of prayer to ask the Almighty to bestow upon him a conviction regarding the authenticity of the record in question. Only after a sincere supplication and spiritual conviction with respect to the report would the great Imam include the given narration in his work.[2] Similarly, another great hadith scholar Ahmad ibn Hanbal is said to have taken three hadiths directly from the Blessed Prophet –upon him blessings and peace- in a dream.[3]

Sufism and Islamic Jurisprudence (Fiqh)

Fiqh literally denotes knowing, understanding and comprehending. During the early days of Islam, the word fiqh would encompass all kinds of knowledge, both temporal and spiritual, a person needed; and one who had amassed an expertise in knowledge in its broadest significance was referred to as a faqih, in the sense of an alim or a scholar. In this context, a faqih was person with insight into the wisdom underlying being and physical occurrences, as well as an intellectual capacity to discern and acknowledge his religious rights and responsibilities. Accordingly, Imam Abu Hanifa defines fiqh as “…a person’s knowledge of the things in favor of and against him with regards to religion.”

The central aspect of this knowledge was to ‘know the Lord’, the knowledge most essential to human happiness. Thus, Abu Hanifa’s writings on creedal topics were later compiled by his students under the title of “al-Fiqhu’l-Akbar”, or ‘the greatest fiqh’. In the early days of Islam, that was what the term fiqh meant. In time, however, when the body of Islamic knowledge became immensely extensive, the word fiqh acquired its terminological sense and scholars of fiqh began to exclude creedal and ethical discussions from fiqh and restricted its usage to practical and legal matters. And today, this is what is meant by fiqh.

Sufism is no different in the sense of relating to the knowledge of things in favor of and against human beings. In addition to the mutual epistemological ground it shares with fiqh, Sufi knowledge includes both internal and external aspects of religious matters. Fiqh gives us information about the external requirements for practical religious topics, such as ritual ablution, ritual prayer, fasting and so forth. As for Sufism, it imparts knowledge with regard to their internal requirements; to clean and purify the heart in order to prepare one for the spiritual contentment, knowledge and inspiration that beckon in the practice of these deeds. The Sufi path thereby functions as the ground for the sincere and perfect devotion to be embodied when offering these deeds. On account of this, Sufism is also called “internal fiqh” (al-fiqh al-batin) or “the fiqh of conscience” (al-fiqh al-wijdani), insofar as it constitutes the spiritual basis and essence of fiqh.

SIMILAR ARTICLES

- WHAT IS ISLAM?

- WHAT IS SUFISM?

- THE FAMİLY TREE OF PROPHET MUHAMMAD SAW

- THE ESSENTIALS OF ISLAMIC FAITH

- FREE İSLAMİC BOOKS READ AND DOWNLOAD PDF

- MORALITY IN ISLAM

There is no doubt that the ultimate goal of the science of fiqh is to ensure that deeds of worship are offered with a certain blend and quality, so that they are accepted in Divine presence. This perfection of quality comes only from a spiritual maturity that Sufism gets one to strive for. In this subtle context, fiqh and Sufism function complementarily to each other; for the fundamental goals of Sufism is making a believer reach metaphysical and spiritual realities through the practice of the external deeds and behaviors fiqh lays down as obligatory. Putting the requirements of fiqh to practice cannot yield the desired results without acquiring the moral and spiritual maturity outlined by Sufism.

In the case of daily prayer, for instance, the science of fiqh describes its external requirements, such as cleanliness and executing the ritual in an acceptable order. Furthermore, fiqh outlines the necessity of intention, which itself is an internal requirement. But in doing so, fiqh does not keep itself busy with the detailed spiritual requirements of prayer, such as purifying the heart from ostentation and jealousy, however necessary they may be for a consummate prayer and complementary to its external requirements. Sufism organizes the inner requirements of prayer and tries to harmoniously combine their external and internal aspects. Since fiqh is a branch of Shariah, imperative for all believers to follow, it basically regulates the outward aspects of religion on which human responsibility is based. Be that as it may, it is the inner quality in which one conducts himself that renders the fulfilling of this responsibility accepted by the Lord; an inner quality the Lord wills to see in His servants.

Scholars of fiqh unearth the religious rulings that regulate all acts of worship, as well as social interactions, like marriage, divorce, trading, and punishments. They examine and systematize these rulings. Complementarily, Sufis provide the moral and spiritual background of these rulings and emphasize the importance of the required spiritual mindset to adopt when offering them. It is none other than the Holy Quran that inspires Sufis in this regard; for it is the Quran that first and foremost places emphasis on the inner and spiritual aspects of deeds of worship.

Of course, all this does not mean that Sufis do not consider the science of fiqh important; nor does it mean that they are not sufficiently interested in Islamic legal studies. On the contrary, great Sufi figures were at the same time competent scholars in the traditional exoteric disciplines, including fiqh. We might, for instance, mention the names of Ghazzali, Ibn Arabi, Rumi, Imam Rabbani, and Khalid Baghdadi in this context.

Those unable to comprehend the real content of outward religious rulings and spiritual realities claim that there is a huge difference and even an unbridgeable opposition between the science of fiqh and Sufism. Indeed, there are some dramatic examples of this situation in Islamic religious history. As far as the relationship between the real scholars of fiqh and competent Sufis is concerned, however, there are a host of cases testifying to their mutual respect and recognition. Disagreement and controversy occurs only between the ignorant who think of themselves as infallibly knowledgeable in fiqh and the crude Sufis who would regard themselves spiritually perfected.

We will show them Our signs in the horizons and within themselves until it becomes clear to them that it is the T/truth. But is it not sufficient concerning your Lord that He is, over all things, a Witness? (Fussilat, 53)

- SUFISM AND NATURAL SCIENCES

Natural sciences, whose basic doctrine maintains that sense perceptions are the only admissible basis of human knowledge and whose scientific data are produced under laboratory conditions, might on the surface seem unrelated to Sufism. But the reality of the matter is not quite so.

Every kind of scientific activity that aims at understanding the underlying wisdoms and realities of beings and natural occurrences, reaches only as far as the point where metaphysics begins; and this is the point where natural sciences and Sufism meet. Sufism peers into and reveals the secrets and wisdoms of all beings, the metaphysical dimensions of the universe in general. It leads human beings to a more reliable, comprehensive, and convincing level of knowledge regarding the Almighty and the worlds. In short, Sufism takes man to the realm of reality.

Natural sciences focus on the material and visible world. Things invented through the study of natural sciences are in fact qualities already embedded in those things by the Almighty. This means that every invention pertaining to material world comes into being as a testimony to the power and might of the Creator. Proceeding from this point, we can argue that natural sciences help us appreciate the miracles of Divine art.

On the other hand, Islam explores matter together with its immaterial and metaphysical dimensions. The modern natural sciences of today have verged upon this approach. Every novel invention in this material world opens a metaphysical door to new unknowns and leads the human mind to the infinite realm. Man begins with the sensory impressions offered to him by material world, though in the end he is led to the metaphysical realities underneath. This is especially the case in contemporary times; science has made an extraordinary advance to the point of coming face to face with metaphysics. For this reason, the materialist theories of old devised to imprison reality into the strict confines of matter have lost their credibility. Lavoisier’s theory of conservation of mass/matter, for instance, considered an indisputable taboo in the last century, has now lost its validity in scholarly circles. Likewise, ‘the law of the eternity of matter’, one of the most controversial points of conflict between philosophy and religion, is not able to find passionate supporters anymore. Even science now prefers the theory that matter is not an essential, but only an accidental form. That matter is a condensed form of energy has now been established by the breaking of the atom into pieces, whereby it has become clear that what we call “matter” is in reality an energy that is imprisoned in a certain form. In addition, many new scientific discoveries, especially in the fields of physics, chemistry, biology and astronomy, serve to confirm countless facts already mentioned in religious scriptures, first and foremost the Holy Quran, regarding the nature of things.

New discoveries on human genes indicate that every human being has a kind of individual and particular code; just one example among many others that testify to the incapacitating nature of Divine art in creation. Paying tribute to this is Ziya Pasha, a 19th century Ottoman intellectual and poet:

I glorify He whose art makes minds meek,

And whose might leaves the wise weak…

From the beginning of Islam, Muslims were taught and knew the innate weakness of human capacity with respect to the wonders of Divine art. The possibility that, towards the end of time, such scientific discoveries might come close to the level of miracles is also no secret to them. Yet, every new scientific discovery reinforces human conviction of his incapacity at the face of the majestic art of the Almighty, whose infinite wisdom he then feels compelled to acknowledge. It is this human weakness Ziya Pasha brings to the fore when he says:

These Divine wisdoms the tiny mind cannot understand;

For its scales cannot weigh a weight so grand

Sufism reflects on all beings in order to comprehend the metaphysical mysteries underlying their existence; the very threshold natural sciences reach at the end of their inquiries. This interconnectedness renders a positive relationship between Sufism and natural sciences apparent and undeniable.

In fact, the Holy Quran diverts attention to the innumerable secrets and wisdoms in creation. The following Quranic verse, for instance, underlines this fact, declaring,

سَنُرِيهِمْ اٰيَاتِنَا فِى اْلاٰفَاقِ وَ فِى اَنْفُسِهِمْ حَتّٰى يَتَبَيَّنَ لَهُمْ

اَنَّهُ الْحَقُّ اَوَلَمْ يَكْفِ بِرَبّـِكَ اَنَّهُ عَلٰى كُلِّ شَىْءٍ شَهِيدٌ

“We will show them Our signs in the horizons and within themselves until it becomes clear to them that it is the Truth. But is it not sufficient concerning your Lord that He is, over all things, a Witness? (Fussilat, 53) The word “horizons” in this verse points to external world that encompasses the human being. As for the phrase “within themselves”, it indicates wisdoms, lessons, and secrets existent in the biological and spiritual aspects of human existence.

In His Holy Quran, the Almighty highlights the importance of examining external word and thus of paying attention to His signs embedded in His creation. We might mention the following Quranic verses in this regard. “Do they not travel through the earth, so that their hearts [and minds] may thus learn wisdom, and their ears may thus learn to hear? Truly it is not their eyes that are blind, but their hearts which are in their breasts.” (al-Hajj, 46) “And We did not create the heavens and earth and that between them in play. We did not create them except in truth (for just ends), but most of them do not understand.” (ad-Dukhan, 38-39)

As far as the creation of human beings is specifically concerned, the Holy Quran underlines that just like it is in the case of all other beings, the creation of human being is directed to certain purposes and just ends, as indicated by the declaration,

اَفَحَسِبْتُمْ اَنَّمَا خَلَقْنَاكُمْ عَبَثًا وَ اَنَّكُمْ اِلَيْنَا لاَ تُرْجَعُونَ

“Did you then think that We created you in jest and that you would not be brought back to Us [for account]?” (al-Muminun, 115)

From the macro to the micro level of creation, extraordinary manifestations of Divine art exist in every particle. Sufism aims at providing a universal comprehension of all these realities, in the center of which lies human being. In addition to this theoretical aspect, Sufism aims at maturing a believer’s religious and spiritual qualities through certain trainings like the remembrance of Allah, glory unto Him, and a variety of other spiritual meditations. Sufism, therefore, includes both theoretical and practical instructions.

In the Quranic scripture, there are verses that call attention to the wisdoms embedded in the physical world; and every now and then, the Quran resorts to question forms in order to make its statements more emphatic. Even though these emphases may appear to be related primarily to the physical qualities of the things in question, they are not reserved exclusively to that. For that reason, in our inquiries to comprehend the wisdom inherent in the visible qualities of entities, we need a more advanced and able methodology than what natural sciences offer us in this regard. And this fact equally accentuates the need one has to improve the spiritual conditions of his heart in order to make it receptive to this spiritual way of sensing and comprehending. In providing such a possibility and competence for human beings, this is where the Sufi way enters the framework.

As hinted at before, a renowned principle of Sufism considers the visible universe as the manifestation of the Names of the Almighty. Every single being in this world is hence a miracle of art. We might proceed and attempt to write voluminous books to explain the nature and realities of the seemingly ordinary happenings we experience on a daily basis; yet we would still miserably fail in offering a complete picture. When a gazelle eats a mulberry leaf to produce musk, for instance, a silkworm consumes the very same leaf to produce silk. The universe around us abounds in the miracles and signs of Allah, glory unto Him, all within the reach of our observation; though we do not spare sufficient time to properly reflect on them. When one observes a greening grass, a blossoming flower and a tree generously offering its fruits with the purpose of deriving a personal lesson; and when one contemplates on the ways how all these plants take their colors, smells and tastes from the simple earth, one cannot help but be awestruck by the glory of Divine art and power. Sufism encourages human beings to look at the whole creation with an eye to take a lesson. Consequently, Sufis believe that nothing in this world was created in vain, without a purpose, a conviction which they confirm by setting the hearts sail towards that very same purpose.

Similar to the Holy Quran and man, the universe has also come into existence as a composition of the manifestations Divine Names. One might say that all natural sciences ultimately aim towards tapping into the Divine wisdom and law that govern the universe entire, which fundamentally are certain compositions of the manifestations of the Divine Names impressed upon the conditions of the world; as has been stated. Strangely, all natural sciences and most scientists constitutionally suffer from an ingrained weakness to appreciate and duly reflect on these manifestations; as only those who improve and mature their moral and spiritual dimensions, may acquire in their hearts the skill of comprehending the secrets and wisdoms of creation, an existential and epistemological capacity that exceeds far beyond the horizons of natural sciences. To venture beyond these horizons at which natural sciences stop short, Sufism takes the lead; and this is the very point in which the two band together.

It is Sufism that brought Turkish literature into existence, developed and matured it.

- SUFISM AND LITERATURE

Sufism conducts its spiritual operation in the heart and the Sufis reflect the subtle ideas and insights impressed upon their hearts onto various forms of literary arts, including poetry and prose. Bringing these reflections and teachings to life through words, Sufis have had a durable impact on the minds across centuries, leaving behind many extraordinary pieces of artwork, enriched in both content and form. The immense Sufi contribution to literature has aided humankind in gradually reaching a refined depth of aesthetic taste, through giving voice to the deepest and most sophisticated feelings ever accessible to human sensation.

In the history of Turkish literature, there is a tradition called ‘Tekke Literature’, explicitly of a religious nature, which emerged from the lodges of (tekkes) of Sufi orders. The linguistic style of Tekke literature varies from being quite simple and fluent to lyrical and even didactic. Religious and spiritual symbols are embedded in the products of this tradition. Munacat and Nat are two of the most common poetry forms of Tekke literature. The main subject matter of the former is the Oneness of The Almighty (tawhid) and seeking refuge in Him, while the latter is a passionate expression of love and yearning for the Blessed Prophet -upon him blessings and peace-. Despite this seeming difference of content, all forms Tekke literature encourage people to improve their levels of piety, to console and comfort their yearning hearts; and aim at steering them clear from sins and heedlessness, and thereby establishing love, solidarity and peace in society.

Since the tumultuous times of the Mongol invasions, Yunus Emre’s poems have functioned as guidance and consolation for people up to this day. Thorough their poems and other forms of literature, Sufis have offered an immense service in passing religious sentiments onto the following generations and keeping moral and spiritual virtues alive. Khoja Ahmed Yesevi, Haci Bayram Veli, Eshrefoglu Rumi and Aziz Mahmud Hudayi are just some of the leading Sufi authors who not only contributed to the flourishing of Islamic-Turkish literature, but also guided believers through their literary output.

As for the tradition of classical or Diwan literature, it consists of poetic works written mostly in the form of the metrical system referred to as aruz, and expressed in a highly advanced level of artistic style. Despite the fact that it also includes exquisite pieces of art in the form of prose, the main body of the Diwan literature consists of rhymed poetry immersed in Sufi ideas. Sufism’s decisive influence on the Diwan literature is unquestionable, as one can find therein many examples of Islamic spiritual symbolism, skillfully articulated in a highly sophisticated style.

Each poetic form employed in the Diwan literature highlights specific religious notions. Munacat, for instance, is about the Oneness of the Almighty; and especially the ones written by Sufi poets are filled of spiritual enthusiasm. Similarly, in the case of nat, whose main topic is the Blessed Prophet -upon him blessings and peace-, one is met with heartfelt yearnings of prophetic love. Fuzuli, for example, expresses the depth of his longing for the Prophet -upon him blessings and peace- in the following lines from his famous Su Kasidesi (Ode of Water), where he traces the ultimate trajectory of flowing water:

All their lives, dashing their heads against one rock to another,

To reach the grounds He walked, like a drifter, flows water

Consequently, under the great influence and inspiration shone upon by Sufism, many celebrated Sufis of the likes of Rumi, Fuzuli, Naili, Nabi, Nahifi and Sheikh Galib, were able to produced exquisite pieces of artwork.

All this gives an idea of the profound enrichment spirituality has bestowed upon all forms of literary art. The moral and spiritual elements of the Sufi way that figure in literary works have enabled made artistic taste of poetry and prose to reach the hearts of the general public. Testifying to this fact is the eminent contemporary scholar of Turkish literature Nihad Sami Banarli, who says, “It is Sufism that brought Turkish literature into existence, developed and matured it.” The immense influence Sufism has exercised on literary forms may also be observed in the works of poets who did not have any personal affiliation with Sufism. Nabi, for instance, was a poet who usually wrote on profane topics; though he could not stop himself from writing a nat. The first poem that brought Tevfik Fikret fame was in fact a munacat.

The Blessed Prophet -upon him blessings and peace- himself encouraged believers to improve their artistic skills and called attention to this dimension of human existence. He especially acknowledged the great influence of poetry on the heart and mind. According to a hadith narrated by Aisha -may Allah be well-pleased with her-, the Prophet -upon him blessings and peace- had his Companions build a special pulpit for the poet Hassan ibn Thabit in the mosque. Hassan would sit on this pulpit and give poetical responses to the poems written against the Blessed Prophet -upon him blessings and peace-. For Hassan, the Prophet -upon him blessings and peace- said, “The Almighty supports Hassan through the Holy Spirit, as long as Hassan defends His Messenger.” (Tirmidhi, Adab, 70; Abu Dawud, Adab, 87) The fact that Jibril –upon him peace- accompanies the poet Hassan indicates that if an artist sets out to produce something for the sake of the Almighty, he can receive Divine inspiration and confirmation in what he does.

The essential ingredients of human arts are kneaded by Sufism; they represent reflections of human refinement, sensitivity and profundity in various formats. As is visible in history, human arts have decisive effect upon building civilizations.

- SUFISM AND FINE ARTS

Artworks are reflections of human spiritual depth and sensitivity onto concrete entities. In the final analysis, every single human art is a certain reflection of thoughts and feelings existent in the human spirit. Artistic refinement and elegance always goes in parallel with spiritual profundity.

The essential ingredients of human arts are kneaded by Sufism in the sense that they represent reflections of human refinement, sensitivity, and profundity in various formats. As seen in history, human arts have decisive effect upon building civilizations. In effect, nations that reached an advanced level of civilizational progress in the past, accomplished this feat not only with respect to politics, economics, and military, but also with respect to sciences and arts. Muslim history is full of examples of such development. Here, we cannot give a detailed exposition of the spiritual patterns reflected onto many kinds of fine arts. Instead, we will rest content with presenting a brief account of the spiritual motifs observable in certain art forms.

Music

Islam does not disallow the flourishing of characteristics innate to human nature; instead, it regulates them to a harmonic order. Like many other aesthetic forms of art, music is one form through which certain characteristics innate to human predisposition find expression. Thus, as is the case with other forms of art, neither can one unconditionally accept music nor reject it.

Sufis acknowledge the undeniable influence of music on man and make use of this art for praiseworthy ends, as outlined by the basic moral and religious principles of Islam. They lead music towards a heavenly objective and make its content and command address the human spirit, rather than the ego. Accordingly, Sufis approve and practice the types of music that are in agreement with these general principles, and disapprove and disallow the types of music that incite and mislead the ego.

Indeed, when directed towards a good end, whether in the form of harmonious instrumental music or accompanied by the lyric poems of gazel, kaside and ilahi patterns, music plays an essential role in elevating the spiritual level of human beings, as it inspires heavenly thoughts and tastes. In this context, music provides many positive benefits. For example, it increases the listener’s desire for devotion, reminds him of the Almighty, makes him mindful of sins, imparts onto his heart pure thoughts and blessings, and so on. Especially when music is played at the proper time, as one is overcome by a state of spirituality it exercises an even further positive influence on the human spirit. Owing to its constructive effects on also on the human psyche, Sufis have made use of music for ages, along with their use of other positive means. Coming to existence as a result of the religious and aesthetic interest Sufis took in music was a distinct branch of Islamic music, referred to, broadly, as ‘Sufi music’.

We need to mention, however, that there is not a unanimously positive or negative Sufi attitude towards music. While there are some Sufis who absolutely disallow the use of music as a means for spiritual training, there are others who argue that music can be employed for this purpose, so long as certain requirements are followed. They disallow, for instance, the use of stringed musical instruments, but allow the use of percussion, the legitimacy of which they draw from the historical fact that the Blessed Prophet -upon him blessings and peace- allowed his Companions to play the said instruments on certain occasions like battle, in order to spur the Muslim soldiers.

For the sake of refraining from endless debates on this issue, it will suffice to conclude that the use of the melodious human voice is permissible within the religious border lines of legitimacy. It might even be said that endorsing music of the kind is even recommendable within general Muslim circles. It is a natural fact that a call to prayer by muadhdhin with a beautiful voice has a greater impact on the listeners. The Prophet’s -upon him blessings and peace- course of action in selecting the person to call the faithful to prayer implies further instructions in this regard. While Muslims were discussing the proper means to call the believers to ritual prayer, the Blessed Prophet -upon him blessings and peace- saw a truthful dream in which he was dictated the words of the adhan. Though he first informed Abdullah ibn Zayd and Omar ibn Khattab -may Allah be well-pleased with them- of the adhan, he did not, however, entrust the duty of reciting it with the two great Companions. It was rather Bilal –may Allah be well-pleased with him- who was entrusted with the duty, from which one may gather that his strong and beautiful voice would have played a major role in his selection; a duty he upheld so long as he remained alive.

With that said, it certainly cannot be argued that music exercises only a positive influence on human beings. Nonetheless, it would not be correct to reject music altogether, simply based on the fact that it is overwhelmingly used, in our times, as a means to incite and provoke the ego.

The following anecdote gives us a general Islamic strategy with respect to the healthy approach to take with regard to music. Khoja Misafir, a disciple of Bahauddin Naqshbandi says, “I was in the service of the respected Bahauddin and but also fond of music in the meantime. On one occasion, together with a number of his other disciples, we came together and with some musical instruments in our hands, we decided to play music in the presence of our venerated master so that we could learn his position in this regard. So, we put our plan into action in his presence. The master did not prevent us from doing so, but simply said, ‘We do not do this…yet we do not disallow it either.’”

The perceptive strategy of Naqshbandi implies that believers should be mindful and precautious with music; for it might be misused by way of inciting human sensual desires. As far as Sufism in a more specific context is concerned, we need to underline that there should be a balanced and reasonable approach to music, particularly in our modern times. As is unfortunately observable in the practices of some so-called Sufi groups, the content of Sufism should not be reduced simply to chanting and singing.

Architecture

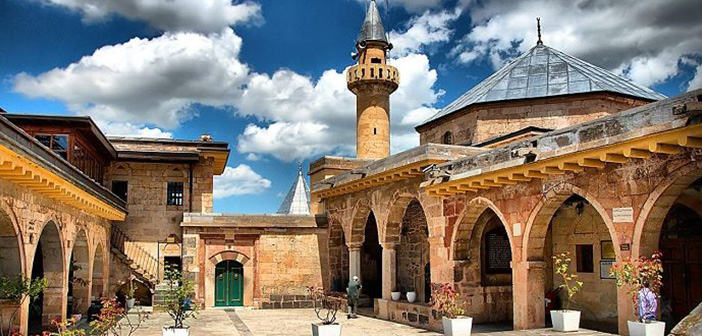

One of the most widely observable works of fine art which stand testimony to the influence of Sufism is indeed architecture. Architecture comes into existence through the combination of mathematical, geometrical and spiritual talents human beings have which is then melted in a harmonious pot. In other words, architecture represents intellectual and spiritual abilities of man reflected onto and embodied in material things, like stone and wood.

Sufism has had a decisive influence on Islamic architecture in more ways than one. We can, for instance, observe this influence vividly in Suleymaniye Mosque and the complementary buildings that surround it. Peering into this architectural masterpiece through a Sufi eye reveals that the spirit of Islam is deep impressed thereon. Its eye-catching magnificence is combined with a profound spirituality, symbolized with many spiritual facets peeking through every inch of the mosque. So skillfully designed are the central dome of the mosque and its surroundings that starting from its foundations up to the dome we can see a gradual symbolic progression multiplicity to unity, to the One (Wahid); the dome which seals the building. The harmony of the central dome with the other domes is quite extraordinary, signifying the Sufi principle ‘unity within multiplicity, multiplicity within unity’. The Suleymaniye Mosque thus attractively embodies a series of elegant marks of spirituality, remarkably epitomizing the transition from the multiple to the majestic ‘One’, and vice versa. In echoing the recitations of the Holy Quran and prayers performed in the mosque, the same dome also symbolizes the Blessed Prophet -upon him blessings and peace- and his function of delivering the Divine message to his followers.

This unique mosque is virtually the meeting point of astonishing human genius and capacity. Tranquility kneaded into majesty in the most consummate fashion has brought a superbly harmonious monument of architectural beauty into existence. With its graceful minarets moving up to the sky, the mosque is like a devout servant who has submissively raised his hands aloft to pray to the Lord.

The internal atmosphere of the Suleymaniye Mosque also casts a profound influence on the human psyche. Many visitors of different religious backgrounds admiringly express the spiritual attraction they feel inside the ambiance of this colossal temple and the comforting inner peace and tranquility that comes over them. It is narrated that the mosque was built on the basis of an order received, in a dream, from the Blessed Prophet -upon him blessings and peace-.

In contrast to mosques of the caliber of Suleymaniye which were built to last until the Final Hour, various types of Sufi institutions such as dervish convents, lodges, and public kitchens served to spiritually enrich the scene of Muslim towns in a different manner. Great and small, many buildings of this type inspire a sense of perishability, simplicity, nothingness, and modesty. They were built in accordance with their function, which means they were spacious enough to facilitate Sufi training; yet they have always been far from giving a sense of majesty, having been built with the intention of inspiring the sense of perishability, instead. Nevertheless, all these buildings offer a display of the manifestations of Islamic spirituality embedded architecture.

Calligraphy

Islamic calligraphy or husn-i hat is the art of handwriting the letters of the Holy Quran in accordance with the set aesthetic criteria and in the most beautiful manner imaginable. To put it in another way, Islamic calligraphy represents an exceptional form of art which was born out of the genuine efforts to handwrite the Holy Quran in the most appropriate manner. Throughout Islamic history, Sufi lodges and convents have played a significant role in developing calligraphy. Sufi circles always supported this form of art and have sponsored many prominent calligraphers, who were able to find an ideal environment in Sufi institutions for both perfecting their skills and receiving further education in the art. Meantime, they would also undergo some kind of spiritual training; for a pure and refined heart has always been considered imperative for calligrapher, to enable him to reflect his talent onto letters with a natural, inborn flow that could find its way into the hearts of admiring eyes. Furthermore, the spiritual maturation of a calligrapher, necessary to obtain expertise in the art, required him to go through a difficult apprenticeship to prove his level of patience and submission. For that, he needed a spiritually matured calligrapher to emulate. Thus, On the basis of such common peculiarities, the art of calligraphy is intimately related to Sufism.

The shared ground between calligraphy and Sufism transpires in the handwriting of a rude and irritable person; it looks skewed and broken, which is a symptom of the spiritual anguish he suffers from deep down. The goal of Sufism is to train and refine the ego and thereby save the human spirit from its tyranny through instilling therein peace and sensitivity. Calligraphers, too, need such peace and sensitivity, as the art of calligraphy is not simply about fine handwriting. Much rather, it is essentially a discipline aimed toward refining souls and to filling hearts with spiritual sensations.

Spiritual strengthening has, in effect, prepared the way for many a gifted artist in attaining to that desired level of maturity and expertise. It was under the spiritual training of Sufi circles that many great masters of Islamic calligraphy of the likes of Sheikh Hamdullah, Karahisari, Yesarizade and Mustafa Rakim attained to that specific maturity. The example below carries great import in reflecting the penetrating influence of Sufism on Islamic arts.

Karahisari, the eminent calligrapher, had been entrusted with the duty of writing the calligraphies of the Suleymaniye Mosque’s dome. He put in his ultimate effort to complete his work as perfectly as possible, so that the calligraphies would live up to the magnificence of the great mosque. He took his job tremendously serious; so much so that towards the end of his work, he lost his sight in both eyes. Once the construction of the mosque was complete and was ready to be opened to public service, the Ottoman Sultan Suleyman the Magnificent said, “The honor of opening this holy mosque to public worship must go to our chief architect Sinan, for accomplishing the feat of building this splendid and marvelous mosque.” As much as he was a master of architecture, Sinan, however, was also a master of modesty. The humble Sinan instantly remembered Karahisari’s matchless sacrifice and politely responded to the Sultan by saying, “Your Majesty, the calligrapher Karahisari sacrificed his eyes while adorning the mosque with his exquisite calligraphies. In my humble opinion, it would be best if you gave him the honor instead!” Sultan Suleyman agreed and gave the unforgettable honor of opening the mosque to Karahisari, amid the heartfelt tears of the onlookers.

In addition to its own artistic standards, the development and continuity of Islamic calligraphy owes a great deal to the spiritual criteria of beauty. From this perspective, the scribing of the Holy Quran and of the description of the personal virtues and the qualities of the Prophet -upon him blessings and peace- (Hilya-i Sharifah) constitute the highest level of perfection in Islamic calligraphy. According to the tradition, only those calligraphers who have proved their unparalleled mastery in calligraphy are given the privilege of attempting to scribe the Holy Quran and the Hilya. It was this profound conduct of respect that made works of calligraphy forcefully attractive to hearts and souls, convincing them to passionately respond to the Divine command “Read!”

Being the fruit of such a sincere theoretical and practical tradition, since its beginning, the art of calligraphy has been taught with no financial charge to determined students. Every calligrapher regards his service of teaching calligraphy as the obligatory almsgiving of this art and never expects any financial return on the basis of his teaching.

In short, a believer who appreciates even a glimpse of the following hadith cannot help but take interest in beauty. The hadith says, “Indeed the Almighty is beautiful and loves beauty.” (Muslim, Iman, 147)

Man craves to express and manifest the inner beauties he nurtures in his inner world. A Muslim artist hence carries a natural desire to allow his profound abilities to transpire in accordance with the given aesthetic criteria and, of course, in a manner that is harmonious with the essence of Islam and clear of the traps of pride and arrogance. All forms of art in accord with the spirit of Islam thus find their due support and protection in Sufi circles. Many forms of fine arts which meet Sufism in the depths of the human intellectual and spiritual world, reach a higher visual and aesthetic level and visual level through the inspirational notions of the Sufi way they absorb in their motifs.

Without the help of spiritual perceptions and feelings, one cannot penetrate into the realm of infinite realities through human reason alone.

- SUFISM AND PHILOSOPHY

Natural sciences investigate physical entities and occurrences piecemeal and try to present their characteristics within the general principles dubbed as ‘laws of nature’. Philosophy is the intellectual discipline that seeks either to combine these scientific principles or to establish more general theories; a branch of learning that makes a constant effort to relate scholarly fields with one another, to expose their deep-down interconnectedness.

From this perspective, philosophy is endorsed as the science of sciences. The sole means philosophy has in its aim to reach a higher truth, however, is the human rational faculty. Although not all philosophical schools assign as high and authoritative a position for human reason as does the philosophical school of rationalism, they nonetheless rely on reason as the only means to search and find truth. Rationalism, in a sense, goes to the extreme point of ascribing a god-like status to reason.

Islam acknowledges human reason or the possession of sanity as one of the fundamental requisites for being held liable for obligations. Still, it also recognizes its innate insufficiency with respect to attaining the ultimate truths, for which it makes it reliant on religious narration or tradition (naql), in contrast to the one-sided philosophical approach to the sources of human knowledge. As a form of Islamic understanding and quest for perfection, Sufism pursues certain metaphysical realities, though its rational endeavor strictly follows the religious tradition and does not venture beyond the limits of spiritual unveiling or insight (kashf). The fact that fundamental Sufi ideas rely on religious principles necessitates the recognition of Sufi intellectual activities as firmly grounded upon the Islamic narrative tradition.

Even though human reason is offered a leeway to capture and reflect on the wisdom of the narrative tradition, its independent activity in demonstrating Islamic precepts is not seen permissible. For this reason, in order to make the human rational faculty as perfectly useful as possible, Islam decrees that it be corrected with revelation, establishing thereby its legitimate field of activity. Still, the general public, or persons who are uncultivated in this regard, are not required to accept every single idea expounded through one’s spiritual insight. Setting the standard here is a Sufi maxim, which declares that “…a spiritual insight is binding only for the person who experiences it and not for others.”

It cannot be claimed, in any way, that the ultimate truth is exhausted by the capacity of human reason; for even after reason lies exhausted in its search, the soul is left unsatisfied and continues to explore regardless. This is a natural and inborn human characteristic. For this reason, nearly all intellectual systems, religious or not, acknowledge this aspect of realities that eludes the immediate rational grasp. Renowned is the fact that metaphysical deliberations constitute a significantly large portion of philosophy. But, again, since they have no other medium than human reason to advance in their search, philosophers leave themselves vulnerable to inconsistency. Furthermore, the enterprise of philosophy is reflexive, as each philosopher begins his work by rejecting or disproving the theories of previous philosophers to establish his own personal position, the egoistic arguments in defense of which often betray the underlying self-centeredness underlying it. Nonetheless, used to accomplish this task is again the same tool; reason, which is never free of inconsistencies.

Human reason is indeed like a two-edged sword; one can use it for both good and evil ends. The same human reason which helps man reach the level of “best model” (at-Tin, 4) may also degrade him to the lowly state of ‘bewilderment’. (al-Araf, 179) This means that human reason needs to come under discipline, which Divine revelation provides. Only when reason proceeds under the supervision of revelation will it lead man to salvation; leaving the guidance of revelation aside, it will only steer man to destruction. In attaining the pleasure of the Lord, it is therefore imperative for human reason to be guided.

History has been witness to many tyrants, with sound rational capacities, who have yet not felt the slightest remorse for committing the most brutal massacres; for they perceived their brutalities as sound, rational behavior. Hulagu Khan, for one, drowned four-hundred-thousand innocent people in the waters of Tigris, without feeling the least remorse. Before Islam, many Meccan men used to take their daughters to bury them alive, amid the silent screams of their mothers that shed their hearts to pieces. Chopping a slave was no different for them than chopping wood; they even saw it as their natural right. They, too, had reason and feelings, just like us, which however were like the teeth of a wheel working the opposite direction, defiant of expectation.

Demonstrated by all this is the natural need human beings have for guidance and being directed, owing to the positive and negative inclinations and desires within them. The direction given, however, must in turn be compatible with the natural predisposition; and this is possible only through education in the light of Revelation, that is the guidance and enlightening of prophets. Otherwise, a direction conflicting with the natural predisposition will only generate evil.

Since they attempt to explain everything by way of human reason, philosophers cannot guide themselves to the right path, let alone their societies to this direction. After all, if the human rational faculty had a sufficiently power to guide man to the straight path, the institution of prophethood and the emergence prophets would have been unnecessary. From this perspective, reason stands in need of the guidance of revelation.

Realizing the inherent insufficiency of human reason, some philosophers have sought other means to search for truth. One of them was the French philosopher Henry Bergson (d. 1941), who instead regarded human intuition as an epistemological means to attain to truth. This notion strikes a tune with what our past fellow Sufis would call ‘inner occurrences’ (sunuhat- i qalbiyya), which refers to the implementation of the heart as the means to obtain real knowledge. Bergson argues that it would be wrong to reject the factuality of inner occurrences received after a certain kind and period of spiritual training. He asserts that it would be logically baseless to refute the feasibility of the knowledge obtained by the heart, since this knowledge, as is the case with Sufi knowledge, is of a different nature that eludes all empirical analysis. This fact indicates that only a small portion of philosophy comes close to appreciating religious and spiritual thought. The majority of philosophers, on the other hand, do not accept any epistemological means to attain to truth other than the human rational faculty, sparing their entire time of day instead to launch into falsifying each other. In contrast to the scattered nature of philosophy, prophets and saints, who are their rightful heirs, are fed by the same, harmonious origin; enlightened through Divine revelation and inspiration. Prophets, as well as saints, are therefore always in agreement with each other.

Ghazzali, the great Muslim thinker, says, “Once I finished my investigations and analyses in the field of philosophy, I came to the conclusion that this field could not provide sufficient answers to my need. I realized that human reason alone could not properly understand everything and that it would not always fail in the attempt to unveil the curtain that covers the visible side of things.” Commenting on Ghazzali’s position, Necip Fazıl Kısakürek adds, “As this great thinker, dubbed ‘the proof of Islam’, had verged upon leaving all kinds of rational and scientific approaches aside and had begun inclining towards the real type of knowledge, he hinted that, ‘…the real solution lies in seeking shelter in the spirituality of the Prophet of the prophets; all the rest is some kind of deception and illusion. And alas, reason is nothing but just limitation!’ This exquisite mind thereupon halted all his questions and found shelter under the spirituality of the Prophet of the prophets, and discovered the infinite.” (Veliler Ordusundan, p. 213)

To be sure, one can reach a certain level of reality the limited power of reason; yet how could such a limited faculty cover the entire reality? Is there not any reality that exists beyond it? Even though philosophy ultimately seeks answers to metaphysical questions it does not offer any satisfactory answers to the above questions. But since Sufism differs sharply from philosophy in springing from the source of Divine revelation, one can find indeed answers find answers therein to these gnawing questions.

It is The Almighty Who created man and Who knows best knows his nature, needs and limitations. This makes Divine revelation necessary for human reason in its avid desire to behold the truth. Beyond the furthest point reachable by human reason, there exist other realms, which disclose their realities to the heart in the form of spiritual unveilings or insights. Attaining to the realm of infinite realities is therefore impossible without the aid of the spiritual.

Knowing is not to look on but solve wisdoms and secrets.

Source: Osman Nuri Topbaş, Sufism, Erkam Publications

[1] Muhammad Salih al-Zarqan, Fakhr al-Din al-Razi wa-ara’uhu al-kalamiyya wa-al-falsafiyya, p. 76 (taken from Muhammad Abid al-Jabiri, Arab-Islam Kültürü’nün Akıl Yapısı, p. 626.)

[2] See Ibn Hajar, Hady al-Sari Muqaddima Fathu’l-Bari, p. 489; Ibn Hajar, Taghliq al-Taliq, V, 421.

[3] See Majmū‘ al-Hadith, manuscript 110a-112b.